Making Reeds

To Flick or Not to Flick: Thoughts on the technique of flicking

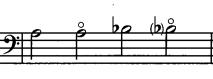

The problems posed by articulating the notes A natural, B flat, B natural, C and D natural (Fig. 1) present no easy answer for the bassoonist. Flicking has been part of bassoon technique for many years. Indeed, there is no question that use of flick keys has greatly improved the smoothness of slurs to these touchy notes. Where disagreement among bassoonists comes is in the use of these keys in articulating the notes in question and, if used, how long these keys are to be held down in relation to the duration of the note.

Much light and heat have been spent debating these points. There are even some bassoonists who judge a player's worth based on whether or not he or she flicks articulated B flats, B's C's and D's! Two ways of solving the problem of cracking when articulating these notes seem to be the most popular and effective. What follows is a brief description of each of my thoughts and suggestions on how the player and teacher can learn from both methods.

Fig. 1

Method I

Bassoonists using this method solve the problem by deploying the flick keys whenever articulation in this range is called for.

Fig. 2 Mozart Bassoon Concerto

The strictest adherents to this method hold the flick key down as part of the regular fingering, even for notes of longer duration.

Fig. 3 Igor Stravinsky Firebird Suite, Berceuse

With this method, the flick keys function almost as octave keys do on other woodwind instruments.

Method II

This method does not involve use of the flick keys to avoid cracking. It relies instead on several other area of bassoon fundamentals to solve the problem. Emphasis is placed on a specific type of embouchure that includes the formation of an overbite and a dropped jaw. Placement of ¾ of the reed blade or less in the mouth is important. The player should articulate the reed near one of the corners of the tip and treat the commencement of the notes as a release of air into the reed instead of an attack. Good breath preparation and off -center tonguing are especially helpful in clearing up a crack. Since this method is more "global" in its approach, it offers many side benefits when used in situations other than when articulating the "flick notes". Intonation, slurring, tone quality and ease of articulation improve.

Each method has its drawbacks. Method I trades in even tone color and pitch that match the notes bordering the "flick notes" for cleanliness of attack. I notice this problem on A and B flat in particular. Consistent use of the flick keys on these notes gives this register a tone quality unlike any other register on the bassoon. Those who initiate a long note with the flick key cannot mask the change in color as the key is released after the beginning of the note. Those who leave it on for the duration of the note give the register a color that matches no other on the bassoon.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Method II is a more complicated approach that may not always be practical in every situation. It assumes a good embouchure, well-balanced reed, superior instrument and bocal as well as other fundamentals mentioned above. In particular, having a good instrument and bocal are important. Some bassoonist with Fox bassoons and newer Heckels have a great difficulty articulating cleanly without using the flick keys, especially when not using a Heckel bocal. Some have been able to solve the problem by thinning the channels of the reed more than usual and by taking less reed in the mouth.

Middle Ground

While Method I solves the problem of cracking, it creates new ones in the areas of pitch stability and tone quality. Thus, it is a less attractive solution than Method II. However, Method II may not be workable for all instruments, reeds and musical passages. Therefore, some middle ground that offers comprehensive solutions to the problem is necessary.

While it is important in teaching to present ideas in a logical, consistent manner, the teacher must also be able to adapt to the individual circumstances of each student and his or her equipment and not simply repeat concepts in a dogmatic, black and white fashion. Students may wish for one "right" answer to a complicated problem, but the teacher always serves the student best by presenting an answer he or she has gleaned from experience and from hearing many sides of the story.

Back to flicking. The best way to achieve clean articulation in this register without sacrificing other important attributes of good bassoon playing is:

- Use Method II as a

foundation because of its manifold benefits, if cracking still occurs the teacher should.

- First check embouchure, reed and tongue placement. If the reed is too far in the mouth (many students play with all of the blade in the mouth), or the tongue is hitting in the middle of the tip (especially bad if the tongue goes in between the blades), or the student is not playing with an overbite, change these first. The benefits in other areas will be great and you will save yourself hours of headaches in future lessons if the student does all of this. If the student still crack then;

- Thin the channels of the reed starting from 1/8 of an inch from the tip and go back until the problem clears up.

- Occasionally problems will persist. If the student is using good fundamentals, then Method I is the answer. When using Method I it is best to mask the timbre change caused by the flick key by removing it as soon as possible. When using the high C key to flick, make sure there is play between it and the resonance key underneath and depress the key only until it touches the resonance key.

In addition, there are often some special types of writing for the bassoon that make consistent use of Method II unattractive. The following are some ways I use both methods in my own playing.

Fig. 5 Igor Stravinsky Firebird Suite, Berceuse

Use Method II. Good tone and evenness of pitch and timbre are paramount here. The rest before the entrance makes good breath preparation possible.

Fig. 6 Beethoven, Symphony No. 4

Method I gets the best results here and no one hears the effects on pitch or tone.

Fig. 7 Prokofiev Classical Symphony

Even with short notes Method II keeps the pitch down and the tone round. This one can be tough for those with substandard equipment, however.

Fig. 8 Mozart Marriage of Figaro Overture

Method I is best when technical concerns are of highest priority.

Side Benefits

The side benefits of Method II, especially treatment of the attack as a release of the prepared breath that involves putting the tongue on the reed before starting the note and not hitting the reed with the tongue as you start the note, are manifested in clean attacks on the first notes of these difficult high-register excerpts.

Fig. 9 Ravel Bolero and Stravinsky Rite of Spring.

In conclusion, I wish to emphasize that the teacher must adapt to the specific difficulties facing a student. A Fox 601 plays very differently than a 6000 series Heckel. Articulating a particular school of thought to the student is important, but both student and teacher must be able to adapt to the challenging circumstances that playing and teaching the bassoon in the real world bring.